Something missing in your life? Try drilling a hole in your head

Robert Lund of Brooklyn shows a video of himself on his laptop. The hole in Lund's head was the result of a mugging, and is bigger and more prominent than the holes on those who have had them drilled voluntarily. (Nichola Saminather/CNS)

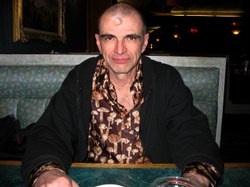

The hole in Robert Lund's forehead was the result of being mugged in 1996. Doctors told him that filling in the hole would have no physiological benefit, and he would have to undergo a separate cosmetic procedure to close it. (Nichola Saminather/CNS)

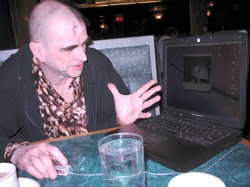

Robert Lund plays a video of himself making the hole in his head pulsate. Although Lund sustained the hole from a mugging in 1996, he says he has felt the same effects as those who have had a hole drilled voluntarily. (Nichola Saminather/CNS)

Robert Lund of Brooklyn plays a video of himself from his Web site. The hole in Lund's head was the result of a mugging, but he says he still feels the effects that others, who have done it voluntarily, claim. (Nichola Saminather/CNS)

Robert Lund of Brooklyn got a hole in his skull as a result of a mugging in 1996. The hole is much bigger than the ones on the heads of those who have them drilled voluntarily, but Lund claims its effects are similar. (Nichola Saminather/CNS)

When Jonathan Cole first read an article in Rolling Stone magazine about people who had holes drilled in their heads voluntarily, he thought they were crazy.

Today, Cole, a student at City College in New York City, has had a 14-millimeter hole in his skull for four years, and he says he would not have it any other way.

Cole, 33, is one of 15 people — 11 men and four women — who participated in a pilot study from 2000 to 2002 of this ancient practice, called trepanation, conducted by the International Trepanation Advocacy Group (ITAG) in a clinic in Monterrey, Mexico. ITAG and trepanation’s first modern proponent, Bart Huges, say the procedure restores the amount of blood in the brain to childhood levels and reduces brain fluid. ITAG says this results in more energy and an increased feeling of consciousness and lessens repression.

The practice dates back hundreds of years and was done for relieving pressure on the brain or for spiritual purposes. Some mystics and their followers believed that the hole helped release evil spirits and that the creation of a “third eye” allowed a person to experience everything in greater intensity. But today, the procedure, which takes 15 minutes and is done under local anesthetic, is regarded with skepticism, and even disdain, by most of the American medical community.

Cole went to Monterrey in June 2002 after stumbling onto ITAG’s Web site. “I was intrigued, because it seemed like the real thing,” Cole said. He said he was on antidepressants and wanted to improve the quality of his life.

At the clinic, the procedure, which cost $2,400, was done with a surgical saw called a trepan. The hole, on the top left side of his head, is covered by curly black hair, so it is not visible. But he said its benefits certainly are.

“If you are watching TV with rabbit ears, you think you have a good signal,” he said, referring to his life before trepanation. “Then you get cable, and you realize how clear it really can be.”

Cole and several other pilot participants admit that life after trepanation is not perfect. But Cole said he felt more like he did when he was younger, more willing to take risks, more open to possibilities and more spiritual. After trepanation, he said, he quit his civil engineering job and started studying music, which had been his passion since childhood. He has also started meditating.

Peter Halvorson, founder and director of ITAG, agreed with Cole’s assessment. Halvorson, who claims to be the first American to have had the procedure voluntarily, drilled a hole through his own skull in August 1973, when he was 27.

Halvorson and Bill Lyons, one of the pilot participants who died of causes unrelated to trepanation in 2002, performed the procedure on a British woman who came to them in Utah. The procedure was shown on ABC’s “20/20” program in 2000. They were charged with practicing medicine without a license, pleaded guilty and were sentenced to three years’ probation.

Halvorson said the experience was an opportunity to get the word out about trepanation, and the woman had been willing to go public. Despite the “sensational” coverage ABC provided and the ensuing court case, Halvorson said the experience did help raise awareness of trepanation and demonstrated that there were people who wanted to have the procedure.

Halvorson, whose hole looks like a slight dent on top of his head, is determined to have trepanation’s scientific value proven. He said he was working with a Russian neurophysiologist on an animal study to determine if there were changes in cerebral circulation after the procedure, paying for the research out of money from his jewelry business. The results will be presented at a neurologists’ conference in St. Louis in July, but until then, Halvorson is keeping mum, except to say that animal studies so far have showed positive results. And ITAG, which is based in Philadelphia, is not referring any more people to be trepanned in Mexico until the results of the study are presented, he said.

“We’re doing this study because we want to determine once and for all whether trepanation makes changes, and if it does, to make the practice universally available,” he said. “I bought a ticket on this horse. I think it is going to win the race. But if the skeptics are right and it doesn’t produce any change at all, I’m willing to accept that and move on.”

Robert Lund, 59, from Brooklyn, was not in the pilot study, but he sustained a hole the size of a quarter in his forehead after a mugging in 1996. Doctors didn’t fill in the hole after removing the pieces of bone because there was no medical reason to do so. Lund reasoned that this means the hole doesn’t cause any harm.

“They’ll reshape your nose, they’ll give you new cheekbones, they’ll fix your boobs,” he said. “But if you want a hole in your head, they won’t do it.”

Dr. John Mangiardi, chief of neuroscience at the Cabrini Medical Center in New York, challenged the notion that a hole in the head increases brain blood volume and that, as blood volume rises, cerebrospinal fluid levels fall. He also said that, as the body replaces brain fluid three times a day, the lower levels seen in MRI scans after the surgeries could have been temporary.

He attributed the positive results seen by several pilot participants to a placebo effect — 30 percent of people who undergo any treatment see positive results, he said. The reason American doctors refuse to do trepanations, he said, although they are not illegal, is the lack of evidence to support the procedure and the risk of liability.

Still, Lund said he had experienced the same effects as many pilot participants — a feeling of lightness and pleasure, of feeling more alive than he had in years. Although this might have been because he had stopped using heroin, which he had been doing for years and, in fact, continued to use for six months after the surgery, Lund said he felt much freer and happier than other people he knew who had stopped taking drugs.

Lund’s hole is larger and more visible than a trepanned hole, and he says he has seen several people's jaws drop particularly since he shaved his head last summer.

“It doesn’t bother me,” he said. “As you get older, you get more damage. This one’s interesting. The hole is here to stay.”

Despite his experience, Lund said he would not have sought out a voluntary trepanation.

“To do that, you have to perceive something wrong in your life, a need that’s not fulfilled,” Lund said. “The people who went to Mexico, I didn’t see any of them living a happy life.”

Halvorson agreed. Like Cole, most of the pilot program volunteers wanted to do more with their lives but didn’t have the “oomph to get out there and do it,” he said. Most of them had tried antidepressants or counseling and found them ineffective, he said.

Halvorson said he was depressed and felt limited before being trepanned. He had also been practicing yoga and learned about other methods by which the brain blood volume could be increased. He met and got to know Huges through friends and learned Huges’ brain blood volume theory. At that time there were no doctors performing the surgery, Halvorson said.

“It made more sense to go ahead and be trepanned than to wait 40 or 50 years with my brain more minimally supplied with blood,” he said. “It made more sense to live my life from the get-go at that level than to wait until some doctor told me it was OK.”

E-mail: nrs2113@columbia.edu